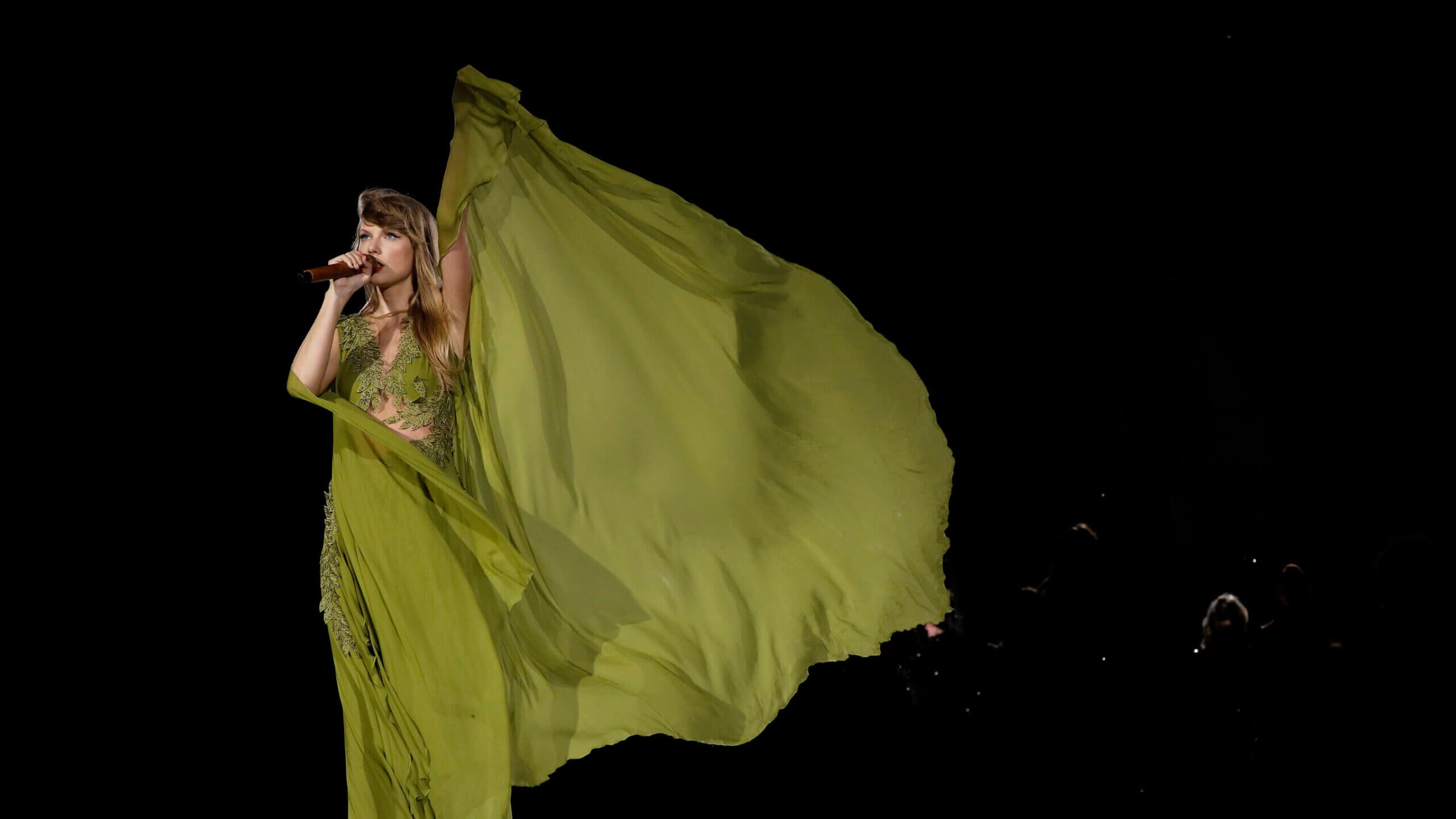

Critics are always bellyaching about the death of the monoculture—we no longer consume the same cultural objects at the same time or in the same way, and as a result we feel disconnected, adrift, lost. The mind-boggling inescapability of Taylor Swift’s latest endeavor—a sixty-date stadium romp known as the Eras Tour—offers one enormous exception. The tour recaps all ten of Swift’s studio albums, presenting each as an epoch, with its own elaborate sets, costumes, and vibes. (The scope of the show reinforces the hysterical demands on twenty-first-century pop stars: be something new every time you show up, or don’t show up at all.) Swift cancelled her previous tour, in 2020; the sweeping concept of this one, combined with the long delay to see her live again, guaranteed that the demand for tickets would be preposterously high. Ticketmaster bungled the rollout so badly that the company received a public talking-to from Swift herself. Not long afterward, the Senate Judiciary Committee held a hearing to investigate whether Live Nation Entertainment, which owns both Ticketmaster and many major concert venues, has an illegal monopoly. The tour, which concludes in November, could, by some foggy estimates, make Swift a billionaire.

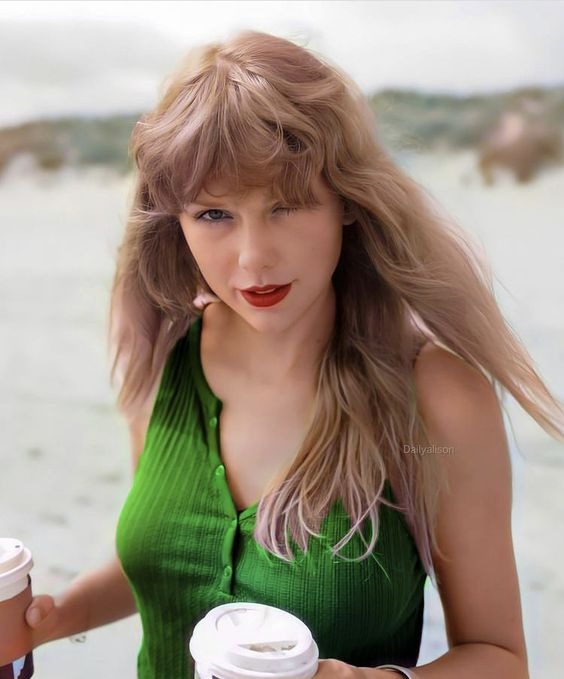

I attended a show at MetLife Stadium, in New Jersey. It was a warm Saturday evening in May, and I wore a cardigan. My daughter, who is about to turn two, had picked out my socks, which had cats all over them—a little wink to the fans, I thought. (Swift loves cats.) Let me tell you: no one was looking at my socks. This crowd had made it fashion. The fits were shimmering and often bespoke. The eye makeup was elaborate. The pavement outside the stadium was dappled with thousands of fallen sequins. Strangers were mouthing the word “slay” to each other. Forearms were wrapped in bracelets featuring Swift-isms spelled out in lettered beads. I was seated in front of two people dressed as fully decorated Christmas trees. (Swift was brought up on a Christmas-tree farm in Pennsylvania.) The crowd was ecstatic, doting, and very sober. The line for chicken fingers was, per my calculation, fifteen times longer than the line for beer.

Swift has for years been a savant of what I might call “you guys” energy, a chatty, ersatz intimacy that feels consonant with the way we exist on social media—offering a glimpse of our private lives, but in a deliberate and mediated way. When Swift addressed the seventy-four thousand people who had gathered to see her, I felt as though she was not only speaking directly to me but confessing something urgent. After one long applause break, she said, “There’s nothing I can say that can accurately thank you for doing that. You just, like, screamed your head off for an hour and a half. That was insane.” Maybe it’s her savvy use of what feels like the singular “you.” When I attempted to explain this feeling to other people, it sounded as though I had been conned. Yet I’d prefer to think of it as an act of kindness: Swift sees each of us (literally—we were given light-up bracelets upon entering) and wants us to know it.

On TikTok, fans discuss each concert with a fervor and knowledge that reminds me of the grizzled heads who spend years analyzing old Grateful Dead set lists. Swift’s show is famously long—more than three hours. By the end, mothers were carrying out sleeping children. I found Swift’s stamina astounding. (She is onstage the entire time, save costume changes.) Some eras translate better than others to the shape and echo of a football stadium. The lusty bite of “Reputation,” for instance, overpowered the aching ballads of “evermore.” There were some nice surprises: Phoebe Bridgers came out to sing “Nothing New,” a wounded song from “Red (Taylor’s Version),” and the Bronx-born rapper Ice Spice performed on a smug remix of “Karma.” Toward the end of the set, Swift does two acoustic songs, on piano or guitar. It’s the only part of the show that reliably changes. That night, she performed “Holy Ground” and “False God.” The latter is one of Swift’s most carnal songs. “I know heaven’s a thing / I go there when you touch me,” she sings.

Swift’s voice has become richer and stronger over the years; its clarity and tone foreground her lyrics. Played on piano, absent the R. & B. production of the studio version, “False God” felt, suddenly, like a reflective song about resigning yourself to failure. Love and sex are a trap, its lyrics suggest; never trust the fantasy sold to you by pop songs:

We might just get away with it

The altar is my hips

Even if it’s a false god.

Swift is sometimes described as “professional,” which feels like a pejorative—it suggests decorum, efficiency, steadiness, and various other qualities that, in general, have nothing to do with great art. She has perhaps been unfairly dismissed as too capable and too practiced, an overachieving, class-president type. I’ll admit that I’ve struggled, at times, with the precision of her work. If you’re someone who seeks danger in music, Swift’s albums can feel safe; it’s hard to find a moment of genuine musical discord or spontaneity. Over time, though, I’ve come to understand this criticism of Swift as tangled up with some very old and poisonous ideas about genius, most of which come from men slyly rebranding the terrible behavior of other men. (Swift sees it this way, too. On “The Man,” she imagines life without misogyny: “I’d be a fearless leader / I’d be an alpha type.”)

The intense parasocial bond that Swift’s fans feel with her—the singular, desperate throb of their devotion—can swing from charming to troublesome. When Swift débuts new costumes, as she did in New Jersey, a wave of glee washes over Twitter. But when she puts out a new song (“You’re Losing Me”) with lyrics that suggest romantic turmoil (“And I wouldn’t marry me either / A pathological people pleaser”), it can provoke vitriol—in this case toward the actor Joe Alwyn, Swift’s former partner. (Weeks earlier, Swifties were outraged after one of Alwyn’s co-stars posted a photo of him on a scooter, which was read as an egregious slight because Swift has been in a public battle with a music executive named Scooter Braun.) It’s hard enough to understand a relationship when you’re inside it; trying to piece together a narrative via song lyrics and a few paparazzi photos seems like a fundamental misunderstanding of human relations. Swift was recently rumored to be dating Matty Healy, of the British rock band the 1975. Healy is, depending on whom you ask, either an irascible provocateur or a disgusting bigot. Some of Swift’s fans deemed him a racist torture-porn enthusiast, owing to comments he made on a podcast, and groused about him after he and Swift were photographed together. Though it would be easy, and maybe even correct, to dismiss this sort of hullabaloo as ultimately innocuous—just people being hyperbolic online, in the same way one might tweet, say, “Taylor Swift can run me over with a tractor”—the swarm-and-bully tactic feels at odds with Swift’s music, which has always lionized the misunderstood underdog. Maybe Healy deserves it. Alwyn, at least, seems innocent. This is the obvious flip side of Swift’s purposeful cultivation of intimacy. From afar, her fans’ possessiveness appears both mighty and frightening.

Still, the intensity of her fandom manifests so differently offline. Swift’s performance might be fixed, perfect (it has to be, of course, to carry a tour so technically ambitious), but what happens in the crowd is messy, wild, benevolent, and beautiful. I was mostly surrounded by women between the ages of fifteen and twenty-five. As Swift herself once sang, on “22,” that particular stretch into post-adolescence is marked by feeling “happy, free, confused, and lonely at the same time.” The camaraderie in the audience invited a very particular kind of giddiness. My best friend from childhood had accompanied me, and when she returned from the concession stand carrying two Diet Pepsis so enormous that they required her to bear-hug them for safe transport, I started laughing harder than I have laughed in several years.

As the night went on, I began to understand how Swift’s fandom is tied to the primal urge to have something to protect and be protected by. In recent years, community, one of our most elemental human pleasures, has been decimated by covid, politics, technology, capitalism. These days, people will take it where they can get it. Swift often sings of alienation and yearning. She has an unusual number of songs about being left behind. Not by the culture—though I think she worries about that, too—but by someone she cared about who couldn’t countenance the immensity of her life. In her world, love is conditional and frequently temporary. (“You could call me ‘babe’ for the weekend,” she sings on “ ’tis the damn season,” a line I’ve always found profoundly sad.) On the chorus of “The Archer,” she sings, “Who could ever leave me, darling? / But who could stay?” Toward the end of the song, she adds a more hopeful line: “You could stay.”

As she sang that “you” on Saturday, she raised an arm and pointed directly to the audience. Swift has written many songs that describe her devotion as a punishment to be endured. “I love you, ain’t that the worst thing you ever heard?” she bellows on “Cruel Summer.” She believes that the force of her affection will push people away. But her fans have remained. They have buoyed her; in turn, she has given them everything. ♦