hen I came to the end of my time as the head of Worcester College, Oxford, and accepted a professorship at Arizona State University, I thought there would be many new opportunities: the chance to devise interesting new courses, ample time for academic research and writing, perpetual sunshine. What I could not predict was the present my wife and I received from our daughter last Christmas: tickets for the opening concert of Taylor Swift’s Eras Tour, which happened to take place in the 80,000-seat football stadium down the road in Glendale.

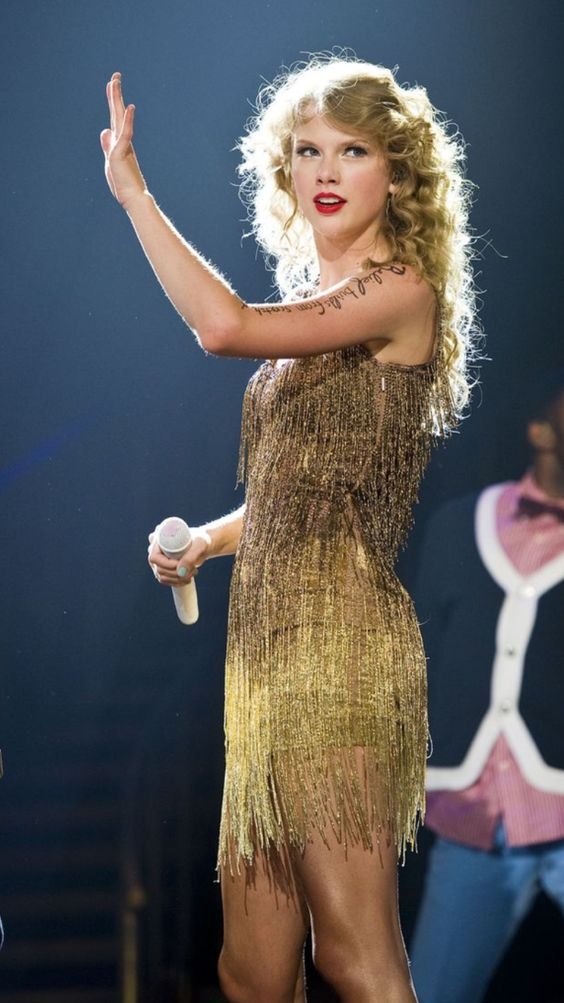

Unlikely as it may seem for a Shakespeare scholar who has reached the age of the Beatles song When I’m Sixty-Four, I have to confess to being something of a Swiftie. And in spite of my insufficiently spangled attire, I had one of the best nights of my life at her concert. The production values and costume changes surpassed anything in Las Vegas, but were themselves surpassed by the energy, charisma and discipline of Swift herself – she worked her way through 44 songs in three-and-a-quarter hours without a break.

Listening to her lyrics, which most of the rapturous (mainly female) audience seemed to know by heart, I came away with confirmation of a thought I first had 15 years ago: this isn’t just high-class showbiz, Taylor Swift is a real poet.

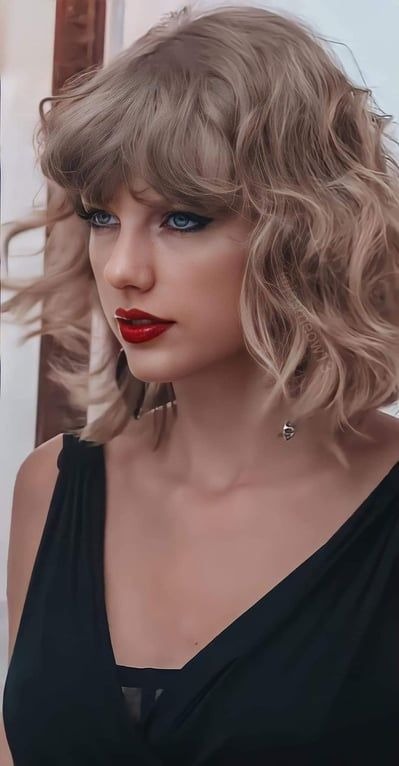

Why Reputation era Taylor Swift was my favourite Taylor Swift

Why Reputation era Taylor Swift was my favourite Taylor Swift

My initiation came in 2009. Browsing in an English bookshop, my ears pricked up to a country-inflected love song being piped from behind the tills. It began with a young girl standing on a balcony in summer air. “A-ha,” I thought, “I know where this is going.” And, sure enough, I had an addition to my lengthy list of Shakespearean references in popular culture:

You were Romeo, you were throwin’ pebbles

And my daddy said, “Stay away from Juliet.”

I walked out with a CD of Fearless, the breakthrough album of the 18-year-old Taylor Swift, hitherto little known outside country music circles. I gave it to my daughter, Ellie, who was nine, and my discovery made me rather cool in the eyes of her friends, none of whom had heard of Taylor, but all of whom eventually became Swifties.

Advertisement

This track, Love Story, is an almost perfect pop song, with its catchy hook, driving rhythm and ingenious use of banjo and mandolin. It would also become a very handy teaching aid when I got back in front of my students at Warwick University, where I was then professor of Shakespeare.

That balcony, for example. Try to find it in the original text. There is no balcony, only “But soft, what light through yonder window breaks?/It is the east and Juliet is the sun.” The balcony was introduced in the 18th century, most famously in a Drury Lane stage production by David Garrick. This was a good way of showing students how Shakespeare has been changed and adapted down the ages.

In Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare more or less invented the idea of the teenager in love (it was an old story, but no previous version made so much of Juliet’s youth). So the play was the ideal reference point for Swift, a young artist whose trademark theme was heartbreak – usually her own. Most of the songs on Fearless have the geeky girl being dumped for a hotter chick, as in the witty You Belong with Me:

She wears short skirts, I wear T-shirts

She’s cheer captain and I’m on the bleachers.

In Shakespeare, death rather than a scantily clad cheerleader is the adversary that takes Juliet from her Romeo. Teenage suicide would have been too cruel a twist for the song, so Swift reworked the ending: her Romeo tells Juliet that he has spoken to her dad and she can “go pick out a white dress”.

In Shakespeare, death rather than a scantily clad cheerleader is the adversary that takes Juliet from her Romeo.

This revision is in the tradition of rewriting Shakespeare to make his darker moments more palatable, a custom that goes back to the late 17th century, when the Irish dramatist Nahum Tate produced a King Lear in which Cordelia is happily married off to Lear’s godson Edgar instead of being hanged at the behest of her evil sisters.

In 2016, as part of the BBC’s programming to mark the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death, I was asked to devote my Private Passions – the Radio 3 equivalent of Desert Island Discs – to music inspired by the Bard. To illustrate the pervasiveness of his influence, I asked to include Swift’s Love Story alongside more highbrow fare such as Wagner’s opera based on Measure for Measure and Richard Strauss’s setting of Ophelia’s mad songs. The presenter, Michael Berkeley, gave his musical imprimatur: “We probably can’t top this,” he said, wryly, as we treated Radio 3 to Swift’s perfect pop song.

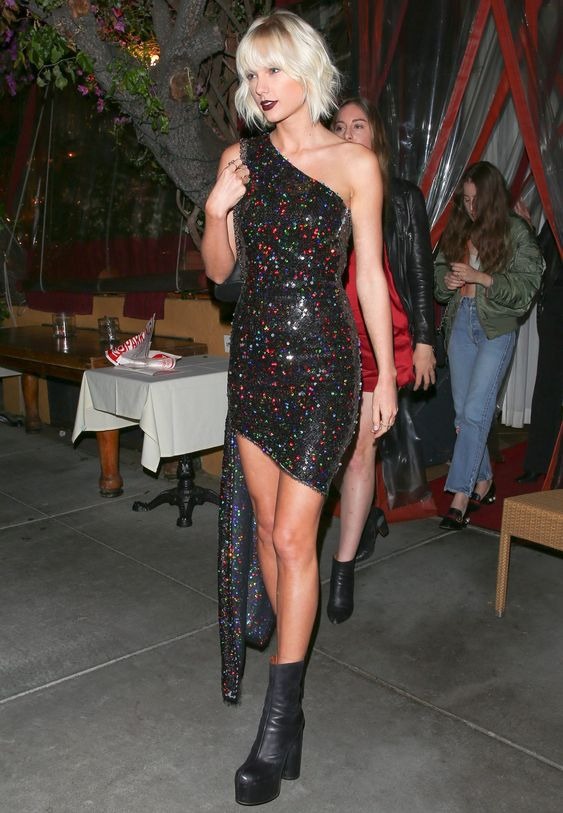

Middle-period rocking, rapping Taylor, I confess, did not really do it for me. But during the pandemic, Ellie, whose passion for Swift has never faded, alerted me to the bonus track released on the deluxe version of the Folklore album, which was garnering rave reviews.

“It’s about the Romantic poets and the Lake District, Dad,” she said, knowing that my other area of expertise is 19th-century poetry, and Wordsworth in particular. Intrigued, I took a listen. The Lakes is a beautifully composed song. It begins:

Is it romantic how all my elegies eulogise me?

I’m not cut out for all these cynical clones

These hunters with cell phones

Take me to the Lakes where all the poets went to die I don’t belong, and my beloved, neither do you.

Those Windermere peaks look like a perfect place to cry

I’m setting off, but not without my muse …

I’ve come too far to watch some name-dropping sleaze

Tell me what are my words worth.

The “name-dropping sleaze” is, one assumes, Scooter Braun, the record executive who sought an astronomical sum for the buyout of the master tapes of Swift’s first six albums – an offer she brilliantly evaded by rerecording them. But “Wordsworth” (as “words worth” appears on the official lyric video) also signals the original Romantic who was the first poet to write elegies – not to mention an epic – that eulogised himself.

Advertisement

Admittedly, I had just argued in my biography Radical Wordsworth that, not long after the poet returned to the Lakes after his years of exile and his wandering into the French Revolution, it was his muse, not him, that died.

RELATED ARTICLE

William Shakespeare

‘This is sacrilege’: Can pop hits, eggplant emojis and Adele save Shakespeare?

But I had also argued that we ultimately have Wordsworth to thank for the Lake District eventually becoming a National Park, where everyone – including mega-famous pop stars – can go to restore their spirits. And be so absorbed in the beauty of the landscape that they will not notice when a mere celebrity is among them. Though, as we discover in Invisible String, Swift’s cover during a holiday to Cumbria was nearly blown at a lunch spot near Windermere:

Bold was the waitress on our three-year trip

Getting lunch down by the Lakes

She said I looked like an American singer.

Invisible String, my favourite song on Folklore, is about Swift’s relationship with English ex-boyfriend Joe Alwyn. It reanimates the old trope of “we were always meant for each other” through a simple but memorable metaphor:

And isn’t it just so pretty to think

All along there was some invisible string

Tying you to me?

Alwyn read English literature at Bristol University, so he would have been fully aware of his ex-girlfriend’s clever use of not one but two literary allusions in these four lines. First there is the closing dialogue of Ernest Hemingway’s great wartime love story, The Sun Also Rises:

“Oh, Jake,” Brett said, “we could have had such a damned good time together.”

“Yes.” I said. “Isn’t it pretty to think so?”

Advertisement

Taylor Swift and her then-boyfriend Joe Alwyn at the 2020 Golden Globes.CREDIT:GETTY IMAGES

And then there is the moment when Mr Rochester finally admits his love for Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre:

“I sometimes have a queer feeling with regard to you – especially when you are near me, as now: it is as if I had a string somewhere under my left ribs, tightly and inextricably knotted to a similar string situated in the corresponding quarter of your little frame.”

Jane Eyre begins with a lonely young girl, who sees herself as an outsider, sitting in a window seat reading a book. For generations, literature has been a resource for teenagers seeking solace amid heartbreak and the confusion of adolescence. Taylor Swift has become their 21st-century voice.

It would seem that Swift has always had a literary sensibility. The earliest song on her debut album is called The Outside. “This is one of the first songs I ever wrote, and it talks about the very reason I ever started to write songs,” she has said. “It was when I was 12 years old, and a complete outcast at school.”

For generations, literature has been a resource for teenagers seeking solace amid heartbreak and the confusion of adolescence.

The song suggests that the way to deal with this sense of exclusion is to carve your own path: “I tried to take the road less travelled by.” The line is a clear allusion to a staple of American middle-school English classes, Robert Frost’s The Road Not Taken: “Two roads diverged in a wood, and I – I took the one less travelled by, And that has made all the difference.”

Advertisement

The image of the road not taken, or less travelled by, recurs in the songs Illicit Affairs and ’Tis the Damn Season on the haunting albums Folklore and Evermore, which for millions became the soundtrack of lockdown. The road of songwriting has indeed made all the difference to Swift.

RELATED ARTICLE

Analysis

Global economy

Welcome to ‘Swiftonomics’: What Taylor Swift reveals about the US economy

By diverging from style to style, not always going down the same well-tried road in the way that so many musicians do, she has kept finding herself new audiences while retaining the loyalty of her original fans.

Swift is famous for hiding “Easter eggs” – cryptic clues – that tantalise her fans. One such was the date of the announcement that she was about to drop her second surprise album of 2020: December 10. That is the birthday of Emily Dickinson, one of whose best-known poems – about a love triangle, a perennial Swiftian theme – ends:

I spilt the dew, but took the morn

I chose this single star from out the wide night’s numbers

Sue – forevermore!

Swift has not revealed whether this was the inspiration for the title track of Evermore, but there is no doubt that some of its lyrics feel extraordinarily Dickinson-like. “The cracks of light” and “floors of a cabin creaking under my step” seem to me to evoke the claustrophobia of the 19th-century New England genius, who has been a muse to some other great modern songwriters such as Paul Simon (For Emily, Whenever I May Find

Her). And lines such as these from Swift could almost have been written by Dickinson herself:

Writing letters

Addressed to the fire

And I was catching my breath

Staring out an open window

Catching my death

And I couldn’t be sure

I had a feeling so peculiar

That this pain would be for

Evermore.

The enduring advocacy of the distinguished critic Professor Sir Christopher Ricks eventually won Bob Dylan the Nobel Prize in Literature. I’m not sure I would yet go that far for Taylor Swift, but watch this space.