The topic of noise is never far away for many helicopter operators. We look at where it comes from, why helicopter noise seems to generate a disproportionate level of complaint, and what can be done to help reduce it.

For years, it’s been one of the most pressing issues in the helicopter industry. Operators field calls from residents complaining about it and must build flight paths in consideration of it, manufacturers are constantly looking at ways to reduce it, and it’s one of the key considerations for the emerging urban air mobility sector. “It” is, of course, noise.

While for those with a keen ear and a love of aviation, the sound of air being beaten through the sky can be a source of pleasure and/or the beginnings of a game of “guess the type” followed by a rush to the window, for much of the general population, it’s more a source of annoyance. According to the Helicopter Association International’s (HAI’s) Fly Neighborly Guide, first produced in the 1980s to help operators limit the irritation caused by the noise their aircraft make, public pressure on authorities to legislate against noise was first noticeable in the late 1970s. It’s been an ongoing battle ever since, with specific hot-spots and flare-ups in the U.S. in the major urban centers of New York, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., as well as over national parks.

These are two locales where helicopter noise seems to be a major issue. In urban areas, you have a multitude of helicopter operations: law enforcement, medical transport, local news, some business transportation, and tourism. And then there’s the more remote, scenic tourist destinations, where those on the ground object to aircraft interrupting their experience in an otherwise serene wilderness. Typically, helicopter tours are the main source of annoyance in these places.

To understand the problem — and how it can be addressed — we need to begin with a look at sound itself. As you’ll (perhaps) remember from physics class in school, sound is a longitudinal, mechanical wave, and it must have a medium (a solid, liquid, or gas) to travel through. It cannot, therefore, travel through a vacuum such as in outer space. As a soundwave moves through a medium, it causes a displacement. This results in a variation in pressure: higher pressure with the crest of the wave, and lower pressure in the trough.

When we hear sound, what we’re actually registering is a change in air pressure. These changes in air pressure cause vibrations in the ear, which are converted into electrical impulses that the brain recognizes as sound. Our hearing is attuned to a certain range of sounds; we can’t hear frequencies that are too low or too high. And at a certain intensity, sound can cause annoyance, what we might call noise.

What’s that noise?

Helicopters generate external noise through several areas. While the engine and transmission certainly generate sound, this is only really heard when the aircraft is up close. “The majority of noise the community is exposed to is aerodynamic in nature, made by the main rotor blades moving through air,” explained Juliet Page, a physical scientist at Volpe, the National Transportation Systems Center. In other words, it is the air itself that is making the noise.

“For rotors and proprotors alike, noise scales with tip speed,” J. Scott Drennan, founder of Drennan Innovation (and former executive with both VTOL and automotive OEM Advanced Air Mobility stakeholders) told Vertical. “In legacy VTOL, tip speeds are very high: 600 to 700 feet per second range — for perspective, the speed of sound is around 1,100 feet per second. That is one of the main drivers [of the noise].”

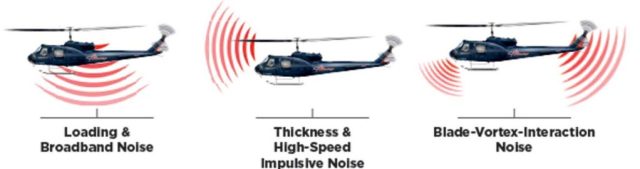

The realm of rotor noise is quite complex, with various phenomena that can be heard. Rotor blades are airfoils. As air passes over them when they rotate, the pressure above the blade decreases and the pressure below increases. This produces the lift that causes the helicopter to rise, but it also produces various airflows that generate different types of sound.

Firstly, there is “thickness noise.” This is created by air displacement as the blade moves through it, and is primarily directed in the plane of the rotor (i.e. horizontally). There is also “loading noise,” resulting from the lift and drag forces on the blades. This is largely directed below the rotor.

Also induced is an airflow around the blade itself — a tip vortex. This vortex may be intersected by the next rotor blade rotating around, particularly at lower airspeeds and during descent. The blade vortex interaction (BVI) produces highly impulsive vibrations in the air, directionally aimed down. This “blade slap” tends to be loud and quite annoying for observers.

“The BVI noise is the particularly dominant noise of the helicopter in approach condition, and this is why the approach condition is the noisiest flight condition for the helicopter,” said Julien Caillet, engineer and head of the acoustics department at Airbus Helicopters.

One interesting aspect of the noise issue is that helicopter sounds seem to be particularly annoying to many people, even though they may not actually be as loud as other sounds they are exposed to. Numerous studies have shown that people perceive helicopter noise as being much louder than it really is — almost twice as loud.

Drennan said that human perception of noise is very complex. “Noise is perceived by a person, and each person has their own subjective opinion about what noise is actually annoying,” he said. “Noise pollution is real to the local communities where current VTOL aircraft operate. That will not change with emerging advanced air mobility designs. The question becomes: “Can we get the noise levels right for the value of service provided by these new aircraft?”

According to Caillet, “a reason for annoyance probably lies in the specific noise signature of the helicopter,” rather than the decibel level of the noise itself.

Page said people respond to the “frequency and repetitive nature” of helicopter noise. The aircraft also emit low frequency vibrations that “may not be heard, but they can be felt.” This may add to the annoyance factor. “Sound radiating out into the community may not be noticeable in the helicopter [itself],” she added.

Flying Neighborly

Helicopter noise is clearly perceived as a problem in some areas, so what has been done about it?

In 1981 HAI published its Fly Neighborly Guide, and this was followed by the launch of its “Fly Neighborly Program” the following year. A voluntary noise abatement program, it was “to be implemented worldwide for all types of helicopter operations, and large and small operators.” The stated objective of the Fly Neighborly Guide is to provide helicopter pilots with “noise abatement procedures” to minimize the effects of helicopter noise emissions that are affecting communities. Of course, safety concerns are also stressed.

In terms of helicopter operations, there were a few obvious solutions. Aircraft are quieter if they are further away. HAI determined that when flying at 1,000 feet, the sound is half that heard on the ground when flying at 500 feet. Flying different routes, away from populated areas, would result in fewer complaints.

“We encourage pilots to voluntarily fly low-noise operations where safe and feasible,” said Page. However, she noted that, “sound is vehicle specific” — so one set of guidelines may work to reduce the noise created by one helicopter type, but not another.

The FAA introduced noise certification standards in 1988, and these have been revised over the years.

Industry, academia and the government have undertaken research to further refine noise abatement procedures. According to Drennan, one of the goals was to check the acoustics on maneuvering to better understand the effect of flight operations. “How do takeoffs, landing, approaches, and hovers affect perceived noise?” he said. “Flying differently can change the noise problem.”

The results of this research have been gratefully received by HAI.

“For the last four years or so, the HAI Fly Neighborly Program has been working on taking the research . . . and bringing it into the hands of pilots and operators, so that they can use the knowledge and science of helicopter acoustics in their daily operations and help reduce noise impacts in communities,” said Page. She added that HAI is also “developing more model-specific guidance for different types of helicopters.”

In terms of addressing specific complaints with a community, the first thing for operators to do is to acknowledge the problem. Let the people who are being impacted know their concerns are being heard.

“Community outreach and engagement can mitigate some of the noise problem,” said Page. “Helicopter operators can go out into the community and explain what they are doing, such as: ‘We’re flying this route, rather than that route over a school or park.’ If you listen to people’s concerns, they respond. There are a lot of places where you can actively engage with the community. People will feel empowered.”

These discussions can also help people realize the positive impact being made by these flights, Caillet pointed out. “If the helicopter is useful for you or the community — and you or the community can benefit from it – then you are much less annoyed.”

If all else fails, public complaints in the U.S. could be directed towards an aviation noise ombudsman at the Regional Administrator’s Office.

A quiet evolution

In addition to adapting operations and community engagement, there have been many physical changes made to aircraft over the years to try to ameliorate the issue of helicopter noise.

“Over the last few decades, manufacturers have introduced lower-noise rotor blades,” said Page. Perhaps the most dramatic example of this is Airbus’s “Blue Edge” rotor blades, which feature on the recently-certified H160. The blades feature a dramatic swept-back tip to reduce the noise generation of BVI.

Another evolution has taken place at the rear of aircraft. Airbus’s Fenestron encloses the tail rotor, reducing sound and enhancing safety. MD’s famous NOTAR does away with a tail rotor entirely, and just last year, Bell revealed it was developing a groundbreaking electric anti-torque system using multiple fans embedded in the tail, rather than a single rotor.

Another technological advance that will impact the noise issue is the evolution and use of the new generation of hybrid and electric VTOL aircraft. Given as they are largely designed specifically for the urban environment, the consideration of noise — and keeping it to a level at which the public will accept their near-constant presence — has been central to their development.

“We are definitely trying to take benefit of these new technologies [developed for the urban air mobility market],” said Caillet. “For example, with this new architecture with the mini rotor, trying to lower speed . . . [and] trying to play on the design of the rotor itself, because we have this additional degree of freedom in terms of design which is possible today.”

Another intriguing element in urban air mobility is the use of electric power in many designs. “The advantages of the more electric aircraft that are coming out today are that we’re using distributed electric propulsion,” said Drennan. “[We’re] creating lower tip speeds in hubs that have smaller diameters and distributing those hubs throughout the airframe. Lower tip speeds mean less noise.”

Other technological advances include the use of enclosed or ducted rotors, exotic blade shapes, and dynamic hub phasing, which is more readily applicable with more electric designs. “Ducts provide a barrier for sound,” said Drennan. “Duct noise is known to be directional. When a duct tilts, the noise profile changes, sometimes for the better given certain operational environments. Ducted rotors, blade shaping, hub phasing and rotor tip speeds change the tonality and frequencies of the emitted sound and can often lessen the typical helicopter thumping noise. Noise now better blends into ambient urban noise and may well go unnoticed.”

However, it is easier to incorporate such elements into the clean-sheet design of a new urban air mobility aircraft than a conventional helicopter. What does the future look like for those that fly them?

“Communities across the world are sensitive to noise, which is increasingly considered as a type of pollution that can have implications for health,” said Caillet. “Helicopter noise is no exception, and while significant improvements have been achieved on the latest products in the market, the level of public acceptance towards the helicopters is still low.

“Manufacturers, operators and pilots continue to work on noise reduction solutions and the replacement of old fleets should also be encouraged as a means to take advantage of the latest technology developments. I believe this will greatly contribute to noise reduction in the future.”