I have this theory that music is usually about five years ahead of the rest of media in terms of its relationship to tech — whether that’s new formats based on new tech, like vinyl to CDs, new business models like streaming, or simply being disrupted by new kinds of artists who use new forms of promotion, like TikTok, in unexpected ways. I’ve always thought that if you can wrap your head around what’s happening to the music industry, you can pretty much see the future of TV or movies or the news or whatever because the music industry just moves that fast.

So, in this episode, Charlie and I walk through a brief history of the music business — which, despite its ever-changing business models, is permanently trying to find something to sell you for $20, whether that’s the music itself, all-access streaming, merch, and even NFTs — using Taylor Swift as a case study. We map her big moves against the business of music over time to try to see if this really is the end of an era. And maybe more importantly, to try and figure out if the music industry can sustain and support artists who are not Taylor Swift because streaming all by itself definitely cannot.

Whenever I think about the state of the music industry and its business, I find myself coming to talk to Charlie Harding.

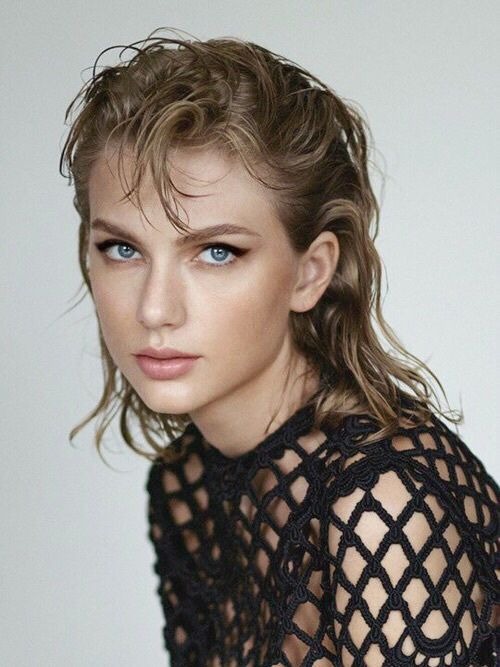

Taylor Swift, interestingly enough, is a great way of looking at the different eras of the music industry, of when they began and when they ended. She has inhabited a lot of them and been able to go with the changes in a way that many artists have not.

She is unusual in that the length of her career spans from the end of the CD era into the streaming era. In many ways, she is at her height and she’s still breaking records on charts. Her career is definitely a good case study across the last almost 20 years.

We have to add some stipulations before we begin a conversation on Taylor Swift. One, I think we both very much like Taylor Swift’s music and we think she’s a good musician.

Very much so. She’s an amazing songwriter.

Two, she is also an incredible capitalist money machine. She’s a great musician, she’s also just very good at making money.

She’s very savvy, yes. Also unusual, because a lot of her peers that go off and make money do so primarily through means outside of music — by starting fashion lines, restaurant chains, or whatever it might be. She has committed hard to the songwriting and music thing, and this next tour is set to supposedly maybe make her a billionaire.

I think that piece of it is the thing that makes her the most unusual. It’s hard to think of another artist at this point that actually monetizes music itself as the primary and richest revenue stream.

That’s the other thing I want to stipulate. If you go back and listen to other Decoder conversations, like the one we had with Steve Boom from Amazon Music, it’s shocking to me how over and over again music itself is undervalued. If you go see an Avengers movie, you might spend $20 on a ticket plus popcorn, or if you watch it on streaming, you might spend an enormous amount of money for those streaming services. Maybe you buy a movie on iTunes for $20 or $30.

With music, the expectation is that it is effectively free. Your Spotify or Apple Music monthly fee is cheaper than Netflix, HBO Max, or whatever else, and you get more. You get the entire catalog of recorded music, in a way that Netflix doesn’t have everything or HBO doesn’t have everything. That dynamic, where you expect more but pay less and the artists are openly struggling, is the most unusual thing about music to me. And then Taylor Swift transcends it all.

With music, the expectation is that it is effectively free. Your Spotify or Apple Music monthly fee is cheaper than Netflix, HBO Max, or whatever else, and you get more. You get the entire catalog of recorded music, in a way that Netflix doesn’t have everything or HBO doesn’t have everything. That dynamic, where you expect more but pay less and the artists are openly struggling, is the most unusual thing about music to me. And then Taylor Swift transcends it all.

The marketplace of music is strange, in that the consumers are pretty happy, the distributors are doing great, and the suppliers are extremely unhappy in general.

By suppliers, you mean the musicians themselves?

Listen to Decoder, a show hosted by The Verge’s Nilay Patel about big ideas — and other problems. Subscribe here!

I mean the musicians, yeah. There is no shortage of stories of artists, musicians, and songwriters being short-shrifted throughout the entirety of the music industry. It’s not the nicest ocean to swim in.

At the current moment, there is a lot of unrest about how much people are getting paid, especially when the average rate per song in streaming is declining for artists, and has been for many years. It seems the only option is to go find radical alternatives and get into the world of crypto in order to survive in music. We definitely live in an era where the actual product is so devalued that all the people that make it are in a state of precarity.

Well, it was similar yet different in many ways. We have three big labels now, but we had four at the time. EMI was eventually bought by Universal, so there was a lot of consolidation on the label side.

The big difference is that the whole industry was a physical goods business; as you said, people were buying CDs in stores. We now live in an intellectual property business, where a lot of these things are never actually even printed. They just get put out for digital distribution. You had a whole different set of distributors, given that there were physical goods, but most of them have shut down. We no longer have our Virgin Megastores selling all of our CDs to us, or Tower Records.

Yeah.

These companies have been replaced by technology distributors — Spotify and all of our favorite tech overlords, like Apple, Google, and Amazon. They are now the distributors of music. There is so much that is similar, especially the labels that have sustained, but how we interact with music and who distributes that music has radically changed.

So Taylor Swift puts out her first CD in 2006. We were five years into the iTunes era at that point. The iPod is out, but Apple is still saying, “Rip. Mix. Burn.” in commercials. The industry is very mad at Apple for this, but the iPod’s ascendancy is there. People are still buying songs for 99 cents on iTunes, and people are still buying CDs in order to rip them onto their computers.

It was an interesting era to launch a music career, because it really was towards the death of the CD era. It wasn’t at its lowest, but it was dropping quickly. 1999 was the height and record profits were declining, yet CD sales were still very large at that point. They were the dominant form of revenue.

Taylor puts out her first record and she wants people to listen to it, so she has to go on radio and on tour. All of that was promotion for you to go spend $12 or $13 on a CD, or 99 cents on a song in the iTunes store. How much of that money went to her as the artist, in general? I don’t think we actually know, but if you were an artist at that time, how much of that money was coming to you?

Well, if you were on a label, you were going to be giving the majority of any revenue from that CD back to the label — as is still done today. You would get a small proportion, 20 percent or less. If you were a songwriter like Taylor Swift, you would also get a cut of the publishing royalties.

Well, if you were on a label, you were going to be giving the majority of any revenue from that CD back to the label — as is still done today. You would get a small proportion, 20 percent or less. If you were a songwriter like Taylor Swift, you would also get a cut of the publishing royalties.

The publishing royalties were smaller then, but you got them for every single song, whereas today, you only get publishing royalties when someone actually listens to a song. The royalty rights weren’t necessarily better, and it just depends on the structure of any given person’s deal, but things were much more assured. There was maybe a simplicity, a clarity, to how the business worked. If you contributed to an album, then you were paid out for someone buying the whole thing, even if you only contributed one song to it. A lot of songwriters liked that model.

It was probably very difficult for an indie artist, because distribution was more challenging then. It was hard to get national or global distribution without a label. You kept more of your revenues — if you own your music, you’re always better off — but it was much more challenging as an independent. Obviously, young Taylor Swift was going to want to have a great record deal so that her music could end up in every single store and car stereo.

You understand the value exchange there, even if the label is taking too much money. I think every artist has always thought that their label takes too much money.

Always.

But you are the artist. Your job was to perhaps show up, perform songs, and work on your image. It was the label’s job to promote you, manufacture CDs, truck those CDs to stores all over the country, manage their relationships with physical media, and distribute it.

It’s very simple. Yeah.

They were a manufacturer in a way that a label today is not. What I’m getting at is that they made physical things. A bunch of Tower Records managers got to go to parties, so they would put your CDs at the front of the store instead of the back. There was some amount of value there that you could see as an artist. “Okay, they’re working to sell my product because they have a financial stake in the product too.”

Right. You could walk into the store and see that your thing was the most billboarded. Absolutely, there was clarity. It didn’t work for everybody, but for the biggest artists, it worked really well.

There are still cracks in the model, right? There are still major disputes between artists and their labels, and there are still lots of people saying, “Hey, this ride is coming to an end, especially around the move to internet distribution of music.”

Surely. People are always going to be upset about their contracts in music. You and some of your listeners can dispute this, but music is not a technology business. Music is an art creation business, a content creation business. I hate that word, but let’s just say it. The way you make more money is often either by getting your stuff to more people or by being some middleman who gets a better, stronger contract.

They got everything for free. I was one of those listeners. I was like, “Napster is the future of the industry!” I think underneath that is a recognition from the listener that your relationship is with the artist. I think that middle step of, “We need to print CDs, we need to promote CDs, we need to sell CDs, and we need to have a relationship with retailers in order to even have the CDs in the stores,” always seemed like a big chunk of revenue that should naturally go to the artist. But instead — and this is us coming to the next era — all of that revenue went to zero. The industry crashed out because of piracy.

There was a nice moment where ringtones started to cushion some of the revenues.

Yes, CDs basically tanked because everybody realized, “I want to listen to all the music, and I don’t really want to pay for it.” CDs were expensive. From a listener point of view, no wonder we were unhappy. I was very budget-constrained at that point in my life, and I used to count the number of songs on an album to think about where I should put my money. If you got 15 songs, well, that’s a lot more than the nine-song record. I wasn’t going to buy the nine-song record because CDs at my local Best Buy were very expensive. So, yeah, it’s no wonder. There was a better option.

To be fair, the big knock on the music industry during the CD era was that CDs were full of filler tracks in order to make them look like a better value than they were. They had raised the prices when they went from vinyl and cassettes to CDs. They were more expensive, so bands would have a one-hit single and a CD full of crap. I could probably name a bunch of ‘90s bands here, but I think we’re already at risk with the Taylor Swift fans. We don’t need a bunch of ‘90s alternative band stans coming after us, but you could throw a dart at your average radio smash ‘90s act and their album would be full of a bunch of filler.

So then that era ends and we’re no longer making all the money on CDs, the revenue for the industry has crashed because of piracy, and for some reason it’s really hard to get a ringtone on a phone, so people will pay 99 cents for a ringtone. That turned into a weird interstitial revenue moment for the industry.

“There was like a 10-year dark era where the industry was searching for the next thing. Ringtones was one of them.”

“There was like a 10-year dark era where the industry was searching for the next thing. Ringtones was one of them.”

There was like a 10-year dark era, the Middle Ages, where the industry was searching for the next thing. Ringtones was one of them.

Any money they could get.

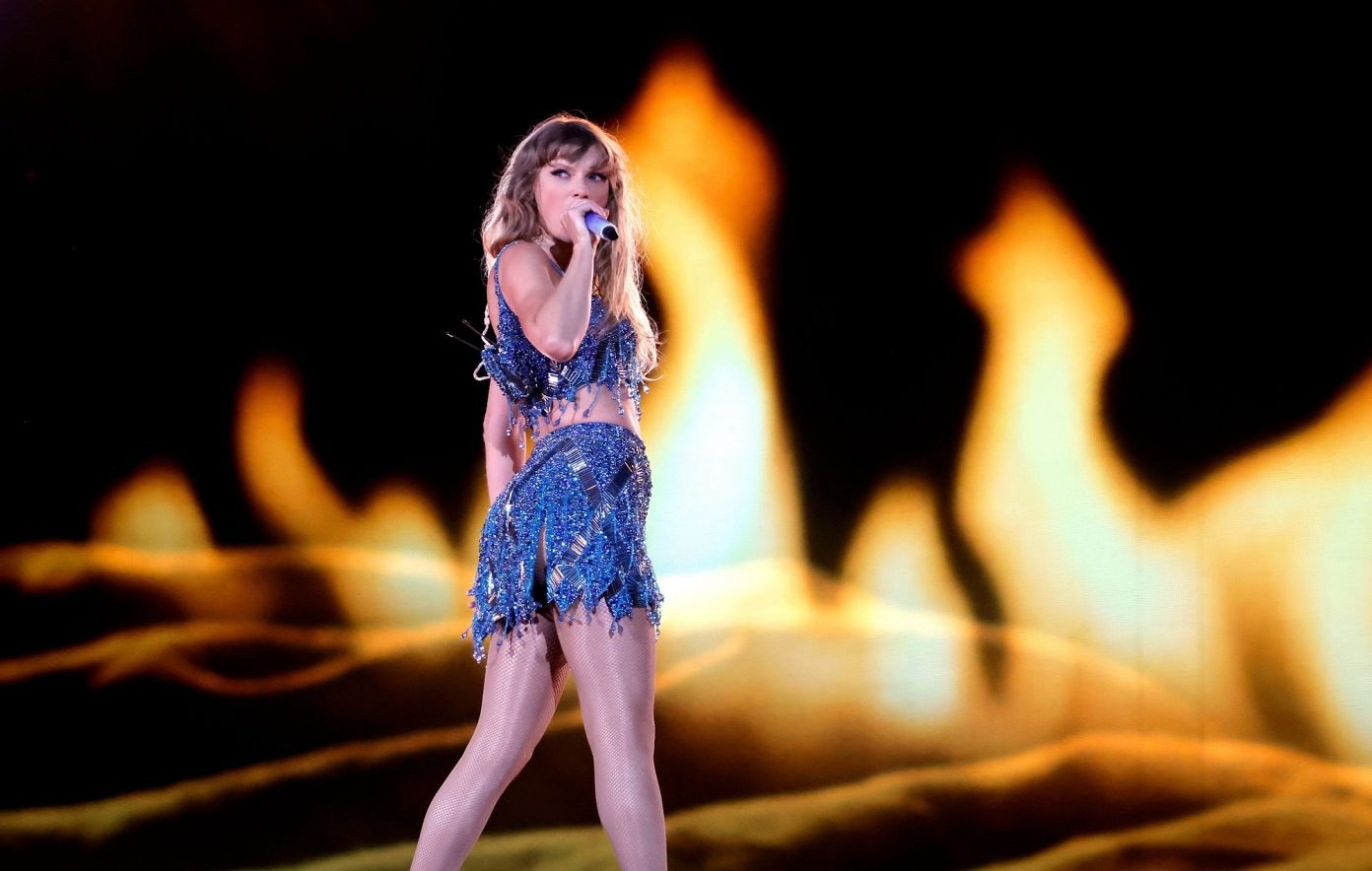

Now before we completely turned to streaming, the revenue model for touring and all the other stuff that artists did was inverted at that time. You went on tour to promote your CD sales and you let radio stations in this country play the music, effectively for free, because that would lead to CD sales. That’s all flipped now.

Well, yeah. Artists and performers didn’t get paid off with radio streams unless they were a songwriter. They still don’t. It’s an unusual part of the licensing arrangement in the United States, and it’s not common elsewhere. But yes, you were promoting the thing that you could sell. We now live in a world where you make the thing and give it away for basically free in the hopes that people will come and join you on your tour, and that’s where you’re going to make all your money.

Just to put a pin in it, highlight it, circle it, bold, italic, and underline that inversion. It used to be that you sold the music, and all the other stuff was just promotion for the music as this thing you sold. Now, here in 2023, the music is marketing for you selling everything else — your concert tickets, your merch, your NFTs, whatever it is. As we go through this chronology from the CD era until now, that is the inversion that Taylor Swift and every other artist has had to either navigate through or get destroyed by.

Yeah. She had bumps along the road doing so. She was very hesitant to participate in the new digital era, calling out the ways in which it was set up to exploit artists. She has voiced concern about digital music and streaming for over a decade, and she has taken some very important actions to show herself as an underdog being exploited by big tech companies that just want to take all the money.

Right. I want to talk about the arrival of streaming to music from about 2012 to 2017, and how Taylor Swift consistently pushed back against that business model. In this period she withheld albums from streaming at times, and removed her entire back catalog from Spotify.

So Spotify arrived internationally in 2006, famously as a response to piracy, especially in European countries, where piracy completely destroyed the industry. The idea is that you have to just accept that people want access to everything all the time. What we can sell them is convenience, as opposed to the chaos of piracy. It’s just like, “You’re going to have to deal with it.”

So Spotify launches in Europe, and what they sell you is convenience. You pay them the fee, and then you have access to an all-you-can-eat buffet of all the music in the world. The labels go along with this because functionally, they have no choice. It gets proven out in Europe over time. There were some smaller versions of this business that launched in the United States — RIP Rdio, which was a Verge favorite.

I loved Rdio.

It’s long gone. Spotify then launched in the United States in 2011. How did Spotify do at that moment? Did it seem like the future? I remember Steve Jobs saying, “People don’t want to rent their music. They want to buy their music. They want to own it. They want to have a relationship with it.” This was a religious war inside the tech and media industries. How did that war play out in the beginning?

Well, the most important thing was Spotify getting the buy-in from the entire industry. You don’t have a streaming service unless you have all the music. So, critically, Spotify is just deeply linked to the major labels. They get early options in Spotify and they get guaranteed payments per year early on, so they’re certain that many millions of dollars are going to come into their coffers, even if no one listens to the service. They are certainly desperate and in need of something at this point. They’re making a really big gamble about their future.

It’s not often that a legacy company is able to navigate between the murky waters of a physical goods business to an intellectual property business. I mean, come on, Blockbuster? But the labels, they navigate it.

Do they know they’re navigating it? I think this is a question I always have. Do they know that their business is out the window? It met more needs for a smaller slice of people that were less discerning, and then it just took over everything because it was more convenient. It grew to be the whole market. But I don’t know if the music industry understood that it was gambling away its future in that way.

People’s behavior was going in one direction, and that was, “I want all the stuff, just give it to me.” Now, obviously, there are always going to be collectors. You can serve them too, by the way. I was a collector. I didn’t want to rent, and I wasn’t into the streaming thing. I wasn’t going to make playlists. I wanted all of my music that I’ve ever had.

For some of us, they even created tools that would help you export your music, so that you could grab your entire MP3 library and all your ripped CDs and carry them with you. That helped persuade me eventually, but most of us were just trying to listen to everything that we wanted whenever we wanted. They were smart to follow what the crowd was doing. They just had to figure out how to monetize it.

We’re looking at Taylor Swift and using her career to chart us through this era. Her albums Fearless and Speak Now came out in this time of big disruption, with early streaming and people still buying records. Do you think she, as an artist, understood that this change was coming and was changing her strategy? Because all the way up to Midnights, she has been a master of marketing an album, but nobody knew at the time that this was going to happen. Is she following the standard playbook or is she evolving?

“In the 2010s, with each record release, there seemed to be a major dispute with the streamers.”

Well in the 2010s, with each record release, there seemed to be a major dispute with the streamers. She wanted to get better terms, and she was able to use her clout to bring a lot of attention to areas where other artists were also unhappy about some of these streaming arrangements. A lot of her early records were released on CD, but by Red, there was a lot of pressure to put things on streaming. She said, “No, I’m not going to put it up on Spotify.”