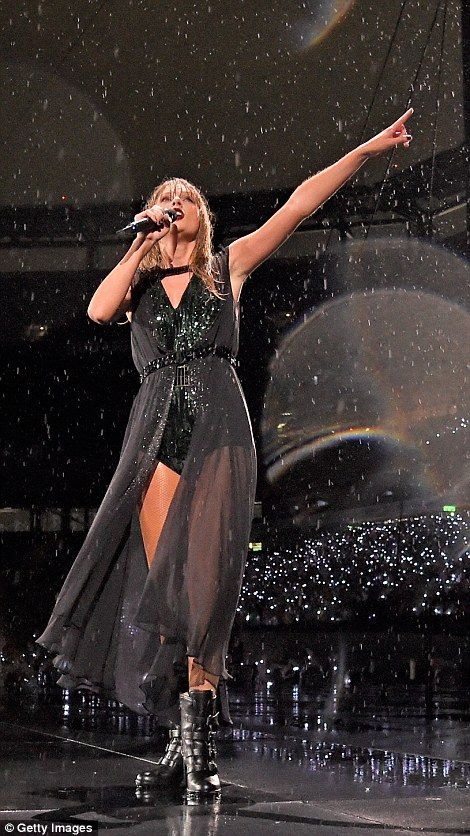

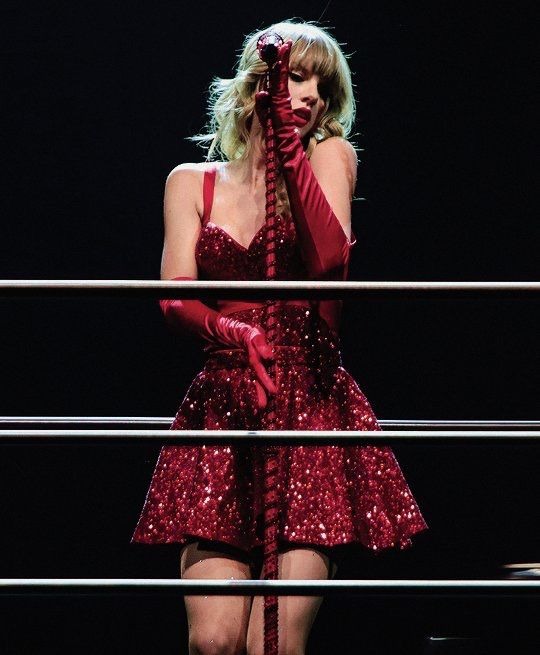

Taylor Swift, public transit savior?

The Chicago Transit Authority said it provided 5.63 million rides for the week of June 4-10, the highest number since the start of the pandemic in 2020, and CTA said that Taylor Swift’s sold-out show at Soldier Field contributed to the spike. The three-night concert generated more than 43,000 additional bus and rail rides, CTA said.

Last month, nearly 140,000 people packed Atlanta’s Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority system to see Swift perform at Mercedes-Benz Stadium over three nights. That’s more than three times the number of MARTA riders on a typical weekend at stations around the stadium.

Last month, nearly 140,000 people packed Atlanta’s Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority system to see Swift perform at Mercedes-Benz Stadium over three nights. That’s more than three times the number of MARTA riders on a typical weekend at stations around the stadium.

Philadelphia’s SEPTA system and New Jersey Transit also got a boost from concertgoers taking mass transit to Swift shows.

Taylor Swift’s shows are known for helping industries such as hotels and restaurants. Raymond James analysts said this week that the shows were “bigger than the Super Bowl” for hotels.

Major concerts and special events often lift public transit, and agencies in Pittsburgh, Minneapolis, Denver, Seattle, Santa Clara, and Los Angeles are all expecting higher ridership from Swift’s tour, said Matthew Dickens, the director of policy development and research at the American Public Transportation Association, an advocacy group.

Many Taylor Swift fans took mass transit because they believed it would be faster than driving. Public transit agencies saw Taylor Swift concerts as an opportunity to draw riders, and agencies made a push to get Swift fans to take mass transit ahead of shows, adding extra service and routes to meet demand. (Philadelphia even brought the Taylor Swift puns for its campaign: “SEPTA is helping riders shake off traffic congestion.”)

Many Taylor Swift fans took mass transit because they believed it would be faster than driving. Public transit agencies saw Taylor Swift concerts as an opportunity to draw riders, and agencies made a push to get Swift fans to take mass transit ahead of shows, adding extra service and routes to meet demand. (Philadelphia even brought the Taylor Swift puns for its campaign: “SEPTA is helping riders shake off traffic congestion.”)

Transit experts say that increasing service, rather than cutting it, will lead more people to take public transit, and that cutting transit service often leads to a downward spiral of declining service and ridership.

“What Taylor Swift is doing, and I thank her for this — although I don’t know she intended to — is proving that if you give people better, reliable transit alternatives, they’ll take it,” said Jim Aloisi, a lecturer of transportation policy and planning at MIT and former Massachusetts Secretary of Transportation. “They would prefer to do that than be stuck in soul-crushing traffic.”

Public transit agencies can hold onto these riders by running more frequent service at off-peak hours and weekends, Aloisi said. They can also cater to riders who aren’t going to offices every day but still work outside their homes at coffee shops and other places.

What transit agencies can learn from Taylor Swift concerts

Public transit is crucial to urban and regional economies, lowering carbon emissions, and access for low-income Americans, who are least likely to own cars.

But public transit agencies still have yet to fully recover from the impact of the pandemic. They face challenges trying to draw riders and fund budgets and improvement projects.

The virus first kept millions of riders off trains, buses and other public transit in 2020. Although Covid-19 is no longer considered a global health emergency, the shift to remote work has led fewer people to commute on mass transit during the week to offices. Inconsistent service and safety concerns among some riders have also kept people off public transit.

Public transit ridership nationwide is down around 30% from pre-pandemic levels, according to the latest estimate from the American Public Transportation Association, although some cities have recovered more quickly.

Public transit ridership nationwide is down around 30% from pre-pandemic levels, according to the latest estimate from the American Public Transportation Association, although some cities have recovered more quickly.

The phenomenon shows that public advertisements and promotional campaigns can be extremely successful in helping travelers go back to transit, said Yanfeng Ouyang, a professor in rail and public transit at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

He said transit agencies should be encouraged to pursue policies such as advertisements and fare discounts to attract riders. Some cities are also experimenting with free public transit rides.